Newcomen Engine

The Talargoch Fire Engine by Robert Jones

The 1660s saw an intensification of mining activity at Talargoch when the hill known as Carreg Faylon (Craig Fawr) had become the legal possession of Eubile Hughes of

Llewerllyd whose family had been fending off illegal miners for some years. He granted leases to mining interests from Derbyshire, Chester and Northop. Until this time

the miners had been doing nothing much more than scratching around on the surface. There were attempts to improve the waterlogged conditions encountered by

driving natural drainage levels and installing pumps powered by water wheels. The problems were exacerbated by the veins having no regard for ownership, which made

it very difficult to organise the drainage of the mine. The details can be followed in J. Thorburn's Talargoch Mine, (British Mining 31, Sheffield: Northern Mines Research

Society).

Deep mining became a realistic proposition in 1712 when Thomas Newcomen built the world's first successful steam mine pumping engine. The machine he erected at

the Conygree Coalworks near Dudley to pump water from the collieries on Lord Dudley's estates is generally reckoned to be the first. In 1986, after more than a decade

of research, the Black Country Living Museum completed a fully working replica at their site on what used to be Lord Dudley's Conygree Park.

Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Cornwall were hotbeds for the development of early steam atmospheric mining pumps. The engineers from those areas started to use

their technical abilities to exploit difficult mines which were rich in ores yet previously considered too wet to be worked profitably. This happened at the Woods Coal Mine

at Ewloe some time between April 1714 and December 1715 when William Probert of Hanmer and Richard and Thomas Beech of Meaford installed a Newcomen engine.

It was a successful venture and they looked for similar opportunities.

In August 1714, a partnership which included Probert and Beech leased the Bishop of St. Asaph's land at Talargoch. By 1736 we know that the Talargoch “Fire Engine”

had been built because it appears on a map attached to the lease taken out by the London Lead Company in that year. The lease explains that the engine used the Welsh

Copper Company’s sough of 1699 as the drain. The sough can still be seen at the bottom of Tir Gwynt, which is the field adjacent to Ffordd Ty Newydd.

The little brick lined adit still serves as the natural overflow for the water from the mine before it makes its way through Roundwood, Llys and into the Prestatyn Cut.

The actual date of the Talargoch Newcomen engine is open to conjecture.

Argument for about 1714

•

The Staffordshire Gentlemen needed to pump Talargoch as soon as possible if they wanted to get to the veins below the water table.

•

They were installing a “Fire Engine” in Woods Coal Mine, Ewloe in that same year and must have been in contact with the suppliers of boilers, cylinders and all the

other parts they needed.

•

By 1717 they had also built one at a lead mine at Yatestoop in Derbyshire.

Argument for about 1724

•

Between 1724 and 1727, Richard Beech had been buying engine parts from Coalbrookdale and they were dispatched to him at Hawarden so he was building an

engine somewhere. No other local mine is known to have had an engine at this time.

Location of the Fire Engine

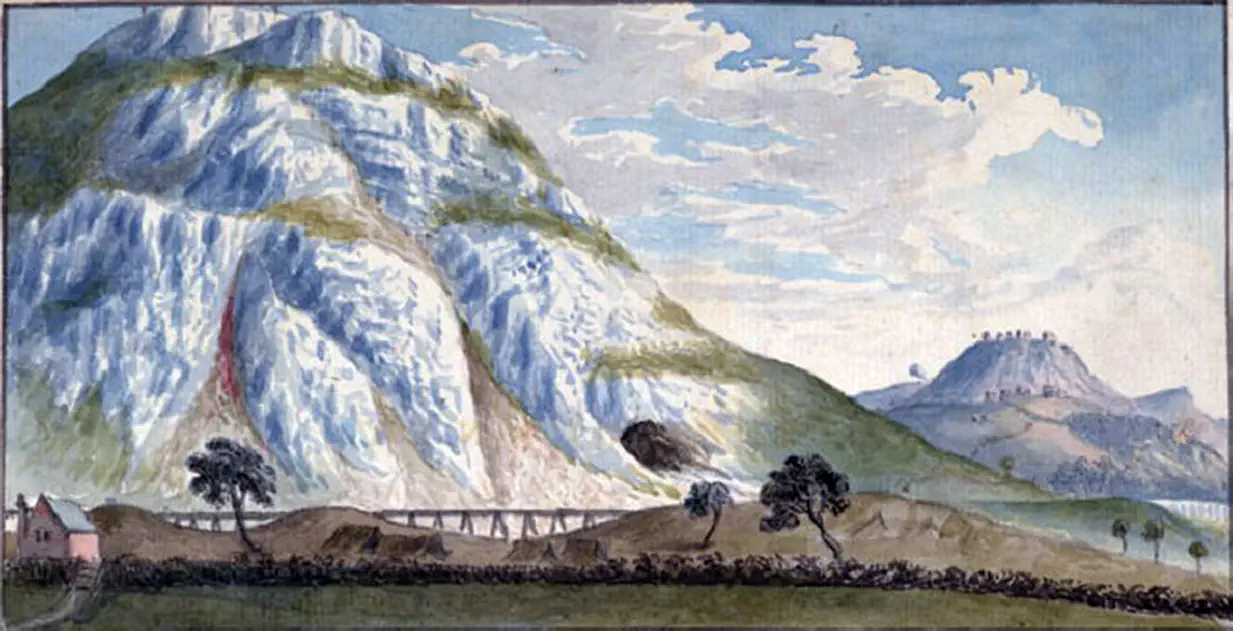

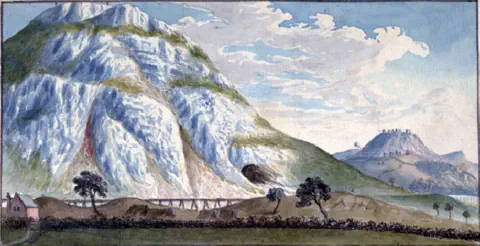

The 1781 colour print of Talargoch and Dyserth Castle in Pennant's The Journey to Snowdon is a gem.

The artist was Moses Griffiths (1747-1819) who travelled with Thomas Pennant on all his journeys in Wales between 1769 and 1790.

In its original form it was a watercolour but was subsequently reprinted in black and white. The focus of interest is Graig Fawr with the red deposits which gave

Talargoch its name. (coch or goch is Welsh for red).

The old mine entrance in the centre is the famous 'cave' known to generations of children as the black hole.

Beyond lies Graig Bach with the ruin of Dyserth Castle atop.

The launder passing behind the spoil in the foreground served the waterwheels which were probably the only means of keeping the mines dry below the level of the

1699 sough (drain). The industrial revolution landed in Meliden sometime between 1714 and 1736 in the shape of that alien brick building sitting as bold as brass in the

bottom left corner—a Newcomen engine house.

In the black and white prints it is easily overlooked, in colour it is a revelation. If you doubt it, just look at the replica Newcomen engine at the Black Country Living

Museum mentioned above and the relationship is obvious.

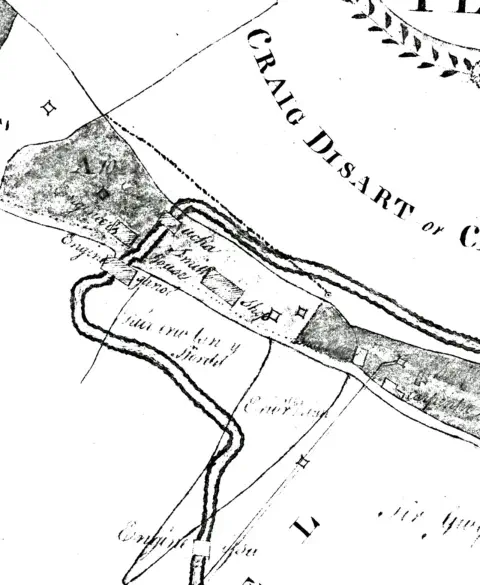

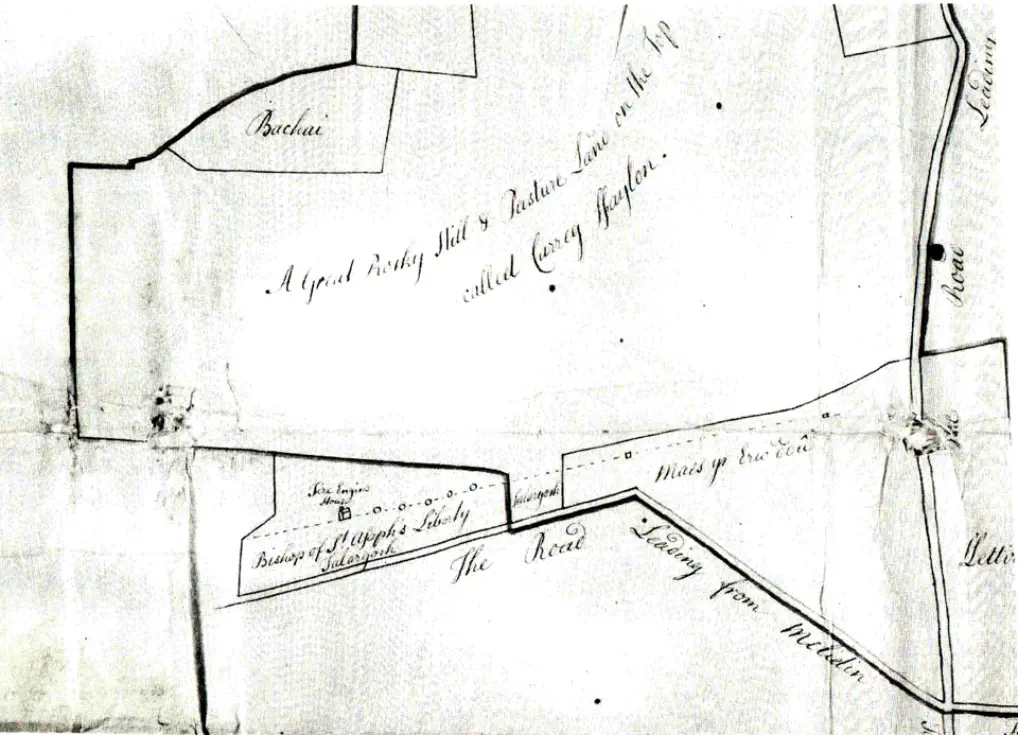

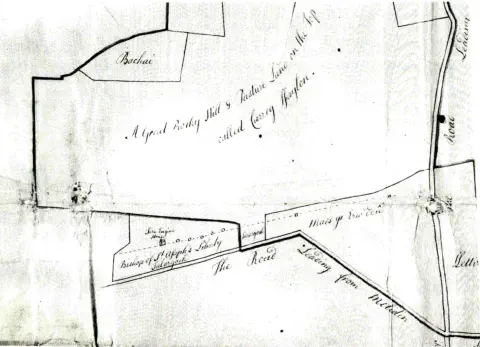

Locating the fire engine shaft is problematic because the contemporary plans would not seem to be particularly accurate with regards to scale. There is a 1736 plan

(below) attached to the London Lead Company's lease which shows the fire engine on the Bishop of St. Asaph's Liberty. (NLW Plymouth Mss. 1586) It was still there

when Pennant and Griffiths visited but may have been empty by that time.

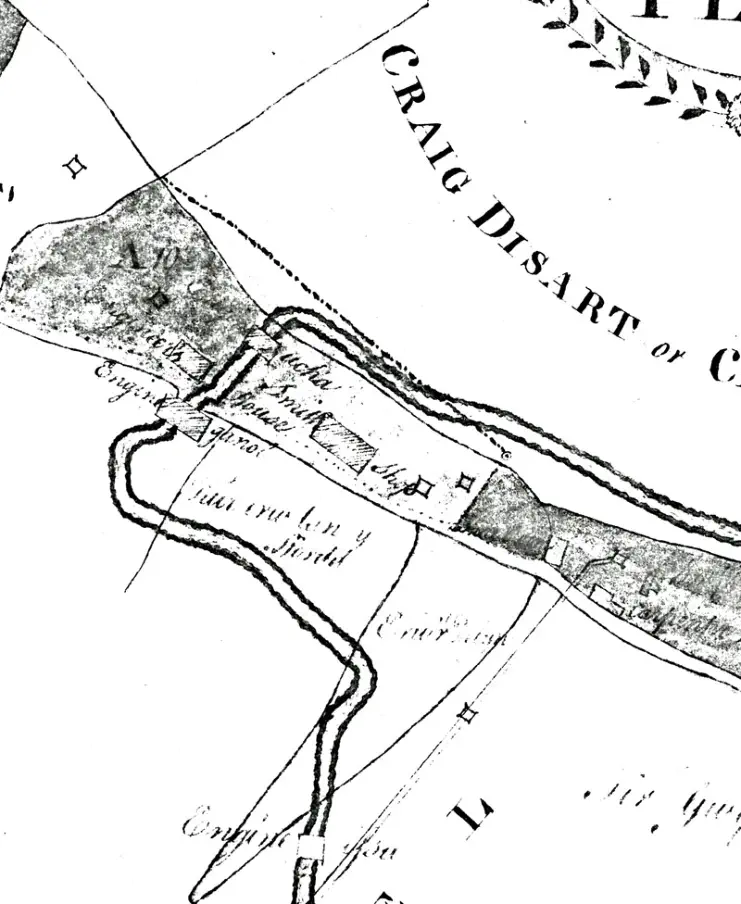

Another plan dated 1799 has far more detail. (UCNW Mostyn

7048) It is the Map of Lands in the Parishes of Disart and

Melidan in the County of Flint which colour codes the various

parcels of land and names the owners.

The shaded area marked A10 corresponds with the Bishop of

St. Asaph's Liberty and the 1750s Panton leat provided the

water for the three water wheels.

The Newcomen engine was sited somewhere here. It may

have been on the engine ucha or engine ganol shaft but

there is another possibility.

Just beneath the A10 inscription is another unmarked shaft.

Unfortunately that shaft does not seem to exist on any of

the surviving underground or surface plans from the 19th

Century.

The Clive engine house has become well known because it

survives. It could be argued that the Talargoch Fire Engine

is of greater historical significance.

Perhaps the impending development of the area might be

preceded by an electrical resistance survey.

R A Jones 2015

Newcomen Engine

The Talargoch Fire Engine by Robert Jones

The 1660s saw an intensification of mining activity at

Talargoch when the hill known as Carreg Faylon (Craig Fawr)

had become the legal possession of Eubile Hughes of

Llewerllyd whose family had been fending off illegal miners

for some years. He granted leases to mining interests from

Derbyshire, Chester and Northop. Until this time the miners

had been doing nothing much more than scratching around

on the surface. There were attempts to improve the

waterlogged conditions encountered by driving natural

drainage levels and installing pumps powered by water

wheels. The problems were exacerbated by the veins having

no regard for ownership, which made it very difficult to

organise the drainage of the mine. The details can be

followed in J. Thorburn's Talargoch Mine, (British Mining 31,

Sheffield: Northern Mines Research Society).

Deep mining became a realistic proposition in 1712 when

Thomas Newcomen built the world's first successful steam

mine pumping engine. The machine he erected at the

Conygree Coalworks near Dudley to pump water from the

collieries on Lord Dudley's estates is generally reckoned to

be the first. In 1986, after more than a decade of research,

the Black Country Living Museum completed a fully working

replica at their site on what used to be Lord Dudley's

Conygree Park.

Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Cornwall were hotbeds for

the development of early steam atmospheric mining pumps.

The engineers from those areas started to use their

technical abilities to exploit difficult mines which were rich in

ores yet previously considered too wet to be worked

profitably. This happened at the Woods Coal Mine at Ewloe

some time between April 1714 and December 1715 when

William Probert of Hanmer and Richard and Thomas Beech

of Meaford installed a Newcomen engine. It was a successful

venture and they looked for similar opportunities.

In August 1714, a partnership which included Probert and

Beech leased the Bishop of St. Asaph's land at Talargoch. By

1736 we know that the Talargoch “Fire Engine” had been

built because it appears on a map attached to the lease

taken out by the London Lead Company in that year. The

lease explains that the engine used the Welsh Copper

Company’s sough of 1699 as the drain. The sough can still

be seen at the bottom of Tir Gwynt, which is the field

adjacent to Ffordd Ty Newydd.

The little brick lined adit still serves as the natural overflow

for the water from the mine before it makes its way through

Roundwood, Llys and into the Prestatyn Cut.

The actual date of the Talargoch Newcomen engine is

open to conjecture.

Argument for about 1714

•

The Staffordshire Gentlemen needed to pump Talargoch

as soon as possible if they wanted to get to the veins

below the water table.

•

They were installing a “Fire Engine” in Woods Coal Mine,

Ewloe in that same year and must have been in contact

with the suppliers of boilers, cylinders and all the other

parts they needed.

•

By 1717 they had also built one at a lead mine at

Yatestoop in Derbyshire.

Argument for about 1724

•

Between 1724 and 1727, Richard Beech had been buying

engine parts from Coalbrookdale and they were

dispatched to him at Hawarden so he was building an

engine somewhere. No other local mine is known to have

had an engine at this time.

Location of the Fire Engine

The 1781 colour print of Talargoch and Dyserth Castle in

Pennant's The Journey to Snowdon is a gem.

The artist was Moses Griffiths (1747-1819) who travelled

with Thomas Pennant on all his journeys in Wales between

1769 and 1790.

In its original form it was a watercolour but was

subsequently reprinted in black and white. The focus of

interest is Graig Fawr with the red deposits which gave

Talargoch its name. (coch or goch is Welsh for red).

The old mine entrance in the centre is the famous 'cave'

known to generations of children as the black hole.

Beyond lies Graig Bach with the ruin of Dyserth Castle atop.

The launder passing behind the spoil in the foreground

served the waterwheels which were probably the only

means of keeping the mines dry below the level of the 1699

sough (drain). The industrial revolution landed in Meliden

sometime between 1714 and 1736 in the shape of that alien

brick building sitting as bold as brass in the bottom left

corner—a Newcomen engine house.

In the black and white prints it is easily overlooked, in

colour it is a revelation. If you doubt it, just look at the

replica Newcomen engine at the Black Country Living

Museum mentioned above and the relationship is obvious.

Locating the fire engine shaft is problematic because the

contemporary plans would not seem to be particularly

accurate with regards to scale. There is a 1736 plan (below)

attached to the London Lead Company's lease which shows

the fire engine on the Bishop of St. Asaph's Liberty. (NLW

Plymouth Mss. 1586) It was still there when Pennant and

Griffiths visited but may have been empty by that time.

Another plan dated 1799 has far more detail. (UCNW

Mostyn 7048) It is the Map of Lands in the Parishes of Disart

and Melidan in the County of Flint which colour codes the

various parcels of land and names the owners.

The shaded area marked A10 corresponds with the Bishop

of St. Asaph's Liberty and the 1750s Panton leat provided

the water for the three water wheels.

The Newcomen engine was sited somewhere here. It may

have been on the engine ucha or engine ganol shaft but

there is another possibility.

Just beneath the A10 inscription is another unmarked shaft.

Unfortunately that shaft does not seem to exist on any of

the surviving underground or surface plans from the 19th

Century.

The Clive engine house has become well known because it

survives. It could be argued that the Talargoch Fire Engine

is of greater historical significance.

Perhaps the impending development of the area might be

preceded by an electrical resistance survey.

R A Jones 2015